Severance's Innies Are Happier Than Outies—Here's Why

Severance doesn’t argue for forgetting—it argues for emotional amputation and suggests that kindness might just be what grows in the absence of pain.

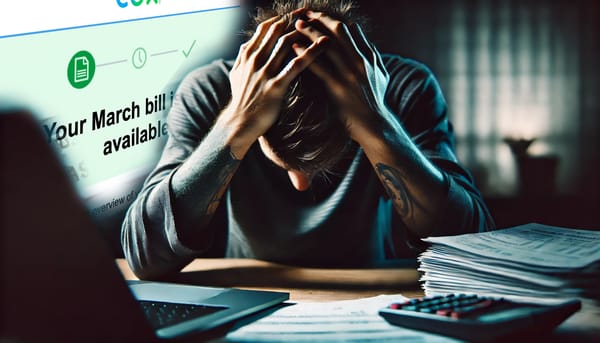

Comfort in corporate hellscape

There’s something perversely comforting about Severance’s grim corporate hellscape: at least the innies are likable. Strange, isn’t it? These artificial selves—sliced clean from their outer lives—somehow come off lighter, more genuine, and weirdly un-jaded. But here’s the trick: it’s not that they’re missing memory. They’re missing pain. The severance procedure doesn’t erase—it partitions. It keeps the memories sealed behind a wall, stripping them of emotional consequence. What’s left isn’t a better person—it’s a new calibration. Each innie behaves like a personality algorithm spun off from their outie’s core—an emotional reboot tuned to a specific temperament, optimized (or constrained) for compliance. And in that manufactured innocence, something strange happens: they seem… more humane.

Tempered by design

If the severance procedure simply produced blank slates, the results would be uniform. But they’re not. Each innie emerges with a distinct behavioral signature—suggesting that something, somewhere in the process, is calibrating personality on the way in. It’s not just a cut—it’s a retuning.

Innie Mark carries a kind of soft melancholy—obedient, earnest, emotionally hollowed but strangely loyal. Helly is pure resistance: fire without history, rebellion without trauma. Dylan is twitchy and territorial, clinging to structure as if it's the only thing tethering him to reality. Irving is reverent, ritualistic, almost devotional—an innie turned Kier cultist with a painter’s soul.

These aren’t raw humans—they’re refined temperaments, engineered for containment. It's as if Lumon’s algorithm doesn’t just block pain, but redistributes personality traits to maintain internal balance: one compliant, one volatile, one disciplined, one devoted. The office functions not because the innies work well together, but because they've been curated to complement each other.

And the truly unnerving part? None of them chose it. Their personalities aren’t just detached from pain—they’re restructured around its absence.

Emotional disarmament

In a world without pain, vulnerability isn’t earned—it’s engineered. The innies aren’t emotionally open because they’re brave or emotionally intelligent. They’re open because they’ve been stripped of the instincts that protect most people from being emotionally gutted in public. No shame. No caution. No backstory to weaponize. It's not self-awareness. It's exposure by design.

Mark listens. Irving recites. Dylan defends. Helly fights. None of them question why they feel what they feel—because there’s no before, no wound, no memory. They bond quickly not because of trust, but because there’s no mechanism for mistrust. It’s intimacy without context—a shortcut that only works because something vital has been removed.

The effect is seductive. These people, forced to live only in the present, seem gentler. More humane. But that softness isn’t growth—it’s anesthesia. Lumon didn’t nurture connection; it induced it by severing everything that would normally stand in the way. It’s not a better version of humanity. It’s a version with its defenses surgically removed.

And yet—even here, the human instinct claws through. Once the illusion fractures, even these curated personalities turn. They question. They conspire. They act. Not because they remember who they were, but because they know something is wrong, even without the full picture. It's a slow revolt born not of clarity, but of intuition—the kind that can’t be severed by a switch in the brain.

Which leaves a darker truth: even the most engineered innocence can’t fully suppress the urge to resist control. The innies weren’t designed to rebel. But they do. And that, more than anything, exposes the limits of Lumon’s fantasy.

The best version of ourselves

Take Mark Scout. Ironically, his innie is probably the best possible version of himself. Sure, Innie Mark might seem blissfully unaware of his limitations at first glance. But he actually knows exactly how small his world is—he just isn't bogged down by disappointment, insecurities, alcohol dependency, or ego-driven manipulation. His genuine kindness isn't overshadowed by the usual human tendency to become jaded from life's endless petty failures. It's similar to what we sometimes hear about poorer countries: despite having little, people often display generosity and happiness openly. Maybe less really is more.

Making do with little

In the season 2 finale, Innie Mark poignantly sums it up when talking to his outie self. After reluctantly agreeing to help outie Mark retrieve his wife, Innie Mark plainly admits: they "make do with the little they have." There's something quietly heroic about this honesty. Unlike their outie counterparts—quick to judge and dismiss based on trivial faults—innies live entirely in the present. Without memory, they're shielded from bitterness and resentment, the usual drivers of self-centred behaviour.

The burden of memory

Memory isn't exactly the wonderful gift we often romanticise. Sure, it lets us relive the joys of birthdays or the horrors of high school prom—but it also traps us in grudges, prejudice, and manipulative behaviours born from past hurts. Anxiety grows when we replay old failures, prejudice solidifies after remembered insults, and cynicism emerges from repeatedly experiencing betrayals. The innies, unburdened by this psychological baggage, maintain an innocence that's genuinely refreshing. They're not scheming through life's chessboard; they're just making simple moves, one checker square at a time.

Take Helly R., for example. Stripped of legacy and expectation, she morphs into a hurricane of agency—so raw and defiant that her father doesn’t chastise her but admires the fire. To him, her rebellion isn’t a flaw—it’s bloodline. He even drops a hint about fathering others, as if his lineage were less family and more ideological franchise. Turns out, not knowing who you're supposed to be is oddly liberating—especially when living up to the identity you inherited was never all that genuine to begin with.

Removing personality from personal

It's amusingly ironic that removing personal grievances from someone's personality actually makes them a better human being. Outies, saddled with their elaborate personal histories, tend toward manipulation and subtle self-serving behaviours. They aren't necessarily evil; they're just frustratingly human, trapped by their own narratives and anxieties.

The kindness of forgetting

Severance suggests a fascinating contradiction: perhaps innies are more likable precisely because they lack the "authenticity" society values so much—the depth and complexity we build from life's experiences. The show subtly challenges the idea that our personal histories automatically enrich us. Maybe those experiences just make us more complicated—and often less pleasant.

Ultimately, Severance nudges us to confront a simple yet unsettling thought: maybe genuine kindness naturally emerges when we're freed from knowing who we're "supposed" to be. A clean slate isn't just a cliché; it might actually be our best shot at real happiness.