Lost Highway Makes More Sense Now Than It Did in 1997

A surreal thriller dismissed by many in 1997, Lost Highway now feels like a haunting mirror—reflecting a world where memory, identity, and perception unravel in real-time.

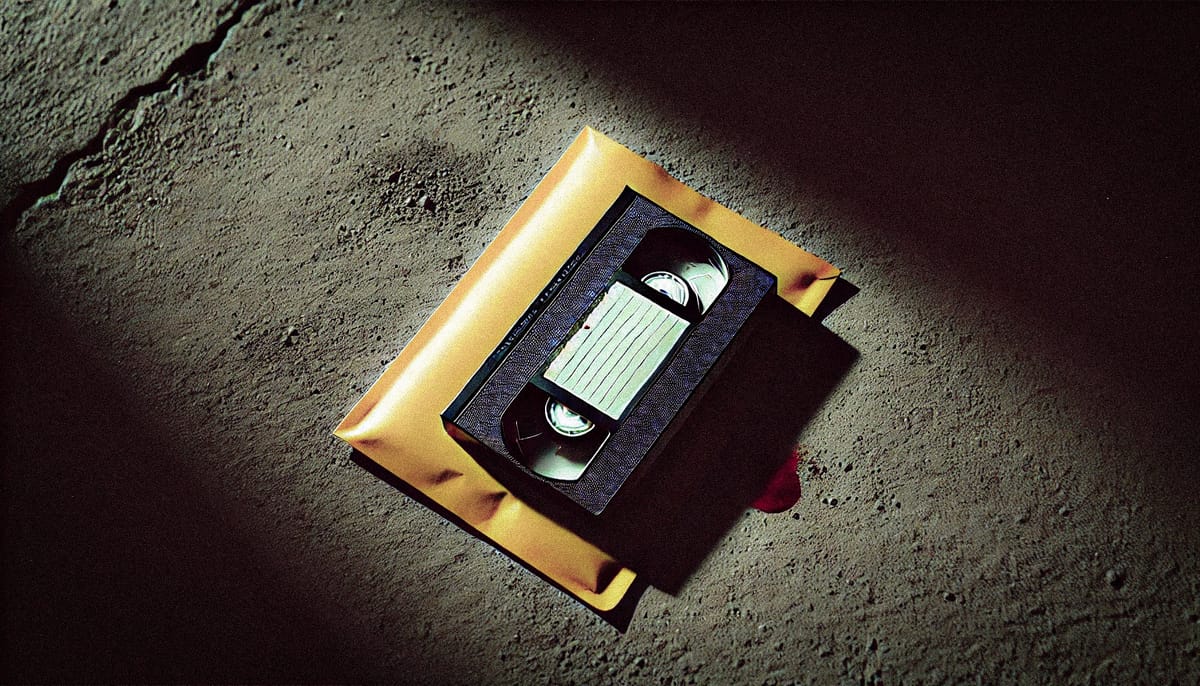

When Lost Highway hit screens in 1997, it arrived like a distorted signal—beautiful, confusing, dark. Today, in a world where people curate their identities and dissociate in plain sight, David Lynch’s film feels strangely more relevant than ever.

At the time, many were turned off by its refusal to explain itself. It’s a polarizing piece, made even more so by the surreal leap it takes—a narrative rupture that would go on to inspire the structure of Mulholland Drive. That later film was no less cryptic, but perhaps easier to love. Lost Highway? It’s a harder pill. But it’s also the one that hits deeper.

The premise hinges on a man who dissociates so completely he becomes someone else entirely. But Lynch doesn’t hold up a sign that says “psychogenic fugue.” Instead, we watch as Fred Madison, played with a quiet, simmering violence by Bill Pullman, tries to escape the crushing weight of jealousy, guilt, and self-loathing. He doesn’t get away with it.

“I like to remember things my own way. How I remembered them, not necessarily the way they happened.”

– Fred Madison

That line lands harder than ever in an era where we all reframe our memories to fit a better narrative. Pullman’s portrayal of a jealous jazz musician is ice-cold and unnerving. His disdain, his refusal to confront the truth, bends his perception until it collapses into delusion. It’s not hard to see our own modern behaviors in this—where reality is often filtered through ego, bias, and curated versions of ourselves. Lynch simply saw it before we did.

Patricia Arquette—haunting, seductive, split—doesn’t just play a femme fatale. She embodies the projection itself. The “her” we see on screen tells us more about Fred than about her. This idea echoes something once said of photographer Diane Arbus: that her images revealed more about her own internal world than about her subjects.

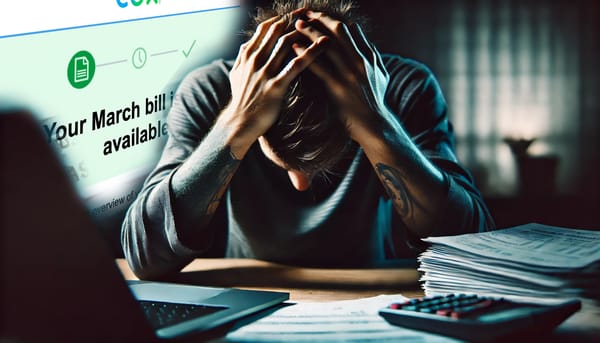

In a world so saturated with narrative—movies, shows, TikToks, Instagram Stories—it’s become second nature for people to see themselves as the protagonist of a film only they’re watching. Ask around. Everybody has a movie where they’re the misunderstood main character. Some even navigate life like it’s an RPG, choosing dialogue and side quests based on audience approval. Lynch didn’t just predict this; he exposed it.

Lost Highway is for those who can sit with surrealism, who don’t need the answer to be handed to them. It’s elliptical, romantic, and darkly poetic—a noir dream folding in on itself. The lesson? We can run from the truth, but we don’t get to leave reality behind. At best, we loop back to the beginning. At worst, we become strangers to ourselves.

“The ideas dictate everything. You have to be true to that or you’re dead.”

– David Lynch

That ethos defined Lynch’s career—and Lost Highway might be one of the purest expressions of it. He never catered. Never explained. He let the ideas speak in symbols, in mood, in sound. And what a sound: Angelo Badalamenti’s eerie score paired with that industrial hum of darkness.

It’s unfortunate this film will never hit the mainstream in the way it deserves. The darkness, the ambiguity, the refusal to spell things out—it’s not built for mass digestion. But if you can stomach the discomfort, Lost Highway is a masterpiece in human perception. A warning, even.

Rest in peace, David Lynch. Your work bent time and revealed us to ourselves—whether we wanted to see it or not.